I spent a month in Paris this spring. It was for work, I hasten to say, as though the Evil Eye is about to jump onto me for my good fortune. Frankly, I was jealous of myself.

Though I had a busy schedule of research and travel and teaching, I also brought with me a little travel pan of watercolours I’d picked up in Konstanz a few years ago. I’m not sure what exactly motivated me to do it, given that I have no experience painting anything and certainly didn’t know what to do with watercolours. In fact, I can’t even say I particularly like the kinds of things people paint with watercolours, and yet some past version of me had been beset by that funny madness that always hits me in art supply stores, and this was the result.

Well, I thought, there must be some place or some person in the city of Paris who would be willing to show me what to do with these paints in exchange for money. An hour later, I’d found what I was looking for: an art school called Le Paon, less than five minutes from my apartment. And just my luck, they were offering a two-day workshop in abstract art that coming weekend. This was good for me, I thought, because I also don’t know how to draw.

The course was taught by a Paris-based artist named Raphaële Anfré. I looked at her website and fell in love with her work. She works primarily in watercolour, but this was nothing like what I knew of watercolour. Her pieces are bold, geometrical, filled in with rich jewel shades of red, orange, yellow, and deep royal blues. Before I could hesitate any longer, I told myself that eight hours in a studio would also be a good way to practice my French.

I could not know it when I was pressing the button to book the course, but that decision was the beginning of a new obsession — and an adventure, and a surprising shift in how I saw myself.

At Le Paon that weekend, Raphaële had us warm up by sketching loosely with coloured pencils, then took us through a series of exercises involving sketching, abstracting out shapes from an image, cutting them out, and playing with them, before recombining them. We then drew the new image we’d come up with, and painted it with acrylic or watercolour — or really whatever else we felt like, since we had the art school’s supplies at our disposal. I was particularly taken with the tube watercolours, something I didn’t even know existed, but which allowed me to get much deeper colours.

The morning after the first day, I woke up, made coffee, and immediately started sketching and painting wild geometric shapes. I couldn’t even bring myself to care about breakfast. And that hunger — to draw, to fill in the drawings with colour — has stayed with me. I started looking up the nearest art stores, buying a pencil or two here, some watercolour paper there, eyeing the good paints, checking out the brushes. At the Louvre, or in various galleries, I began noticing different things about the paintings, like the shades used for shadows, or how the white spaces were made. I began wondering what it would be like to try out oils. I signed up for another course, involving journaling and drawing, that took place just before my month in Paris ended.

I think I’ll be writing about this process for a while, but I wanted to take a moment to reflect, in this space, on a few lessons I took away, both from my classes at Le Paon and from the experience as a whole.

1. Everything needs a warmup

Alright, I feel silly for even writing this, but it was an eye-opener for me. I knew dancers and singers and athletes need warmups. When I teach public writing to university students and academics, I also talk to them about the need for some kind of writing exercising that can function as a segué from doing nothing to working on an actual piece. But I didn’t know that drawing would be well-served by warmups too! There was something freeing about making some very quick sketches in a pencil that couldn’t be erased, looking at an object or a picture from different angles, not thinking at all. It gave my hand a looseness it otherwise wouldn’t have had.

Sometimes the warmup can be rather long. The workshop was a total of eight hours — four on Saturday, four on Sunday. But I finished my final piece on Sunday with an hour still to go. I didn’t want to waste the studio time, so I went to their art book shelf and flipped through Jerry Saltz’s How to Be an Artist. I landed on a stunning 2018 photo of six nude women photographed from behind by Shoog McDaniel, sketched it out very quickly and in a simplified way, then transferred the sketch in an even simpler way onto watercolour paper. Then I painted it in without worrying much about reproducing the photo itself, just trying to make skin tones with the pigments and then letting them do their thing on the page. It wound up being my favourite thing I made that weekend.

Every time I told this story to someone, they said to me, “But you probably needed the other seven hours in the studio to be able to make it.”

2. Pay attention to discards and negative space

I think there’s a ton to be learned from online courses and videos (in fact, I’m thinking of signing up for some of the ones Le Paon offers), but my first course showed me that there’s just so much more to be had from a live teacher. And part of that was in how she taught us to look. Of course, we practiced examining our compositions as a whole to see if there was anything we wanted to add. But the bigger surprise for me was how she noticed interesting shapes in our discarded scraps of paper, in the accidental forms we made when we were paying attention to something else. In the end, I think a few of us used pieces of paper from the discard pile as part of our final compositions.

I’m very fond of using garbage to write. I once took a poetry course with Sara Larsen in which she had us write on whatever scraps we had in our pockets, on bus tickets and receipts and what have you. It was one of the most liberating things I’ve done for my writing, and just typing this out right now makes me want to go hunt down a toilet paper roll and cover it in words. It was cool to see that the idea holds for other media as well.

3. Frames have power

The second workshop I took at Le Paon was dedicated to springtime journaling and drawing. Sophie Gauthier led a meditation and Elise Enjalbert guided us into combining words and images in a notebook. One trick they had that I found surprisingly powerful: they handed out stencils that let us draw large geometric shapes on the notebook pages. We then decided if we wanted to fill the shape with writing and draw around it, or vice versa. Whichever we did, the result of this had a kind of form and deliberateness to it that went beyond whatever it was we were actually putting down.

I was thinking about this little lesson later that same day, when I went to see an exhibition on collective joy at the Palais de Tokyo. The exhibition itself didn’t do it for me. They had tried to incorporate some interactive elements to make it feel more alive, but mostly it was an empty conceptual exhibition on a Sunday night. Most of the art wasn’t memorable, and I couldn’t get past the fact that I’d learned more about collective joy the night before, dancing to Brazilian and Portuguese dance music until 2 a.m. If anything, the best part of the show was a bench where you could read the books that had inspired it, which is interesting, but not exactly transcendent.

But there was one display that kept drawing me. “Art is…” by Lorraine O’Grady was an assemblage of photographs from an interactive performance O’Grady put on in Harlem in 1983. The occasion was the African-American Day Parade, and O’Grady had a float with a large and ornate golden frame on it, as well as actors and dancers who held out other frames, making art out of their own faces and those of passerby. There is more on the piece on O’Grady’s website, as well as a gallery of the images I saw at the Palais de Tokyo. Please do yourself a favour and go look at those pictures, because I can’t do them justice in words. The photos, and the people in them, are playful and joyful and beautiful. They show the power of frames, not to make things into art, but to show the dignity and beauty people already have, whether it’s recognized by the art world (and its institutions) or not.

I was moved a great deal by “Art is…”, but also surprised by something else. What was in the frames looked, well, proportional, arranged, composed. I realised I was looking at a selection of photos, not at the full roll, and yet I couldn’t shake the uncanny feeling that frames also composed the world behind them.

4. Art should be talked about

I work in a brain-obsessed industry, academia. I think it was Ken Robinson who said in a TED talk that academics see their bodies as ways of transporting their brains from place to place. Even though I teach literature, I hardly ever hear anyone talking about art, aesthetics, craft, beauty, form, or making things. (There are a few exceptions to this rule, and I cherish those people immensely.) Part of what was so surprising and refreshing for me in Paris was how much people talked about art.

I mean, sure, in the art school they talked about art, or making a life as an artist. But it came up casually in other ways too. At the university, scholars would chat about their hobbies — painting, or singing. When people learned I was visiting for a month, they asked me what exhibitions I’d seen. A woman I’d just met invited me to her apartment to look at her paintings. Another woman, whom I’d met years earlier, invited me to a vernissage.

Will it sound ridiculous if I say it was refreshing just to be around people talking about art? But it was. And I realised, later, that there’s a power to it too. As I began mentioning to friends and acquaintances that I’d taken an art class, or gotten a bit into watercolour, they reacted. One friend signed up for a watercolour class too. Another started looking up art classes at her local community college. My hair stylist told me, mid-cut, that she used to paint with acrylic, but has been wanting to try pottery for a while. (The woman getting her hair dyed behind me said she wanted to try too, and they were halfway to making a date to go play with clay when I left.)

I saw that a lot of us have creative urges we might want to explore, but if the rules of everyday conversation are that you talk about work or family or politics or the prices of things, we tend to stay quiet about them. But it only takes a little nudge for those urges to come out, and maybe start leading to action.

5. Just go ahead and call yourself an artist already

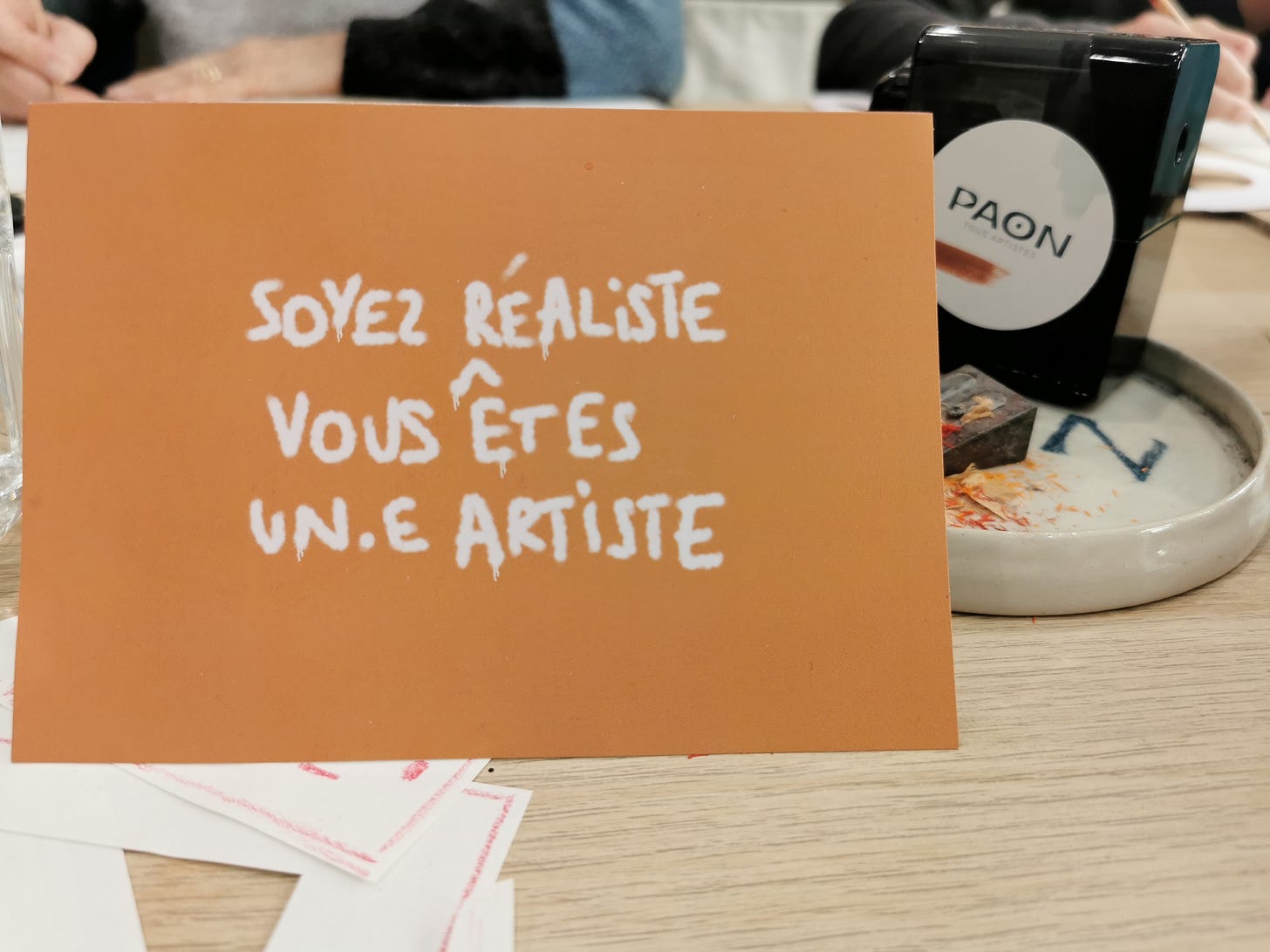

When I arrived at Le Paon for my first class, there was a little postcard at my place setting that read, “SOYEZ RÉALISTE VOUS ÊTES UN.E ARTISTE”. Be realistic, you’re an artist. I laughed. Of course I grew up with the idea that being an artist was anything but realistic, least of all for people who were “intellectual” — a word which was meant, in my home, to refer to people who got good grades at school, not to people interested in ideas. So while I appreciated the sentiment of this card, and had a blast in the course, I certainly was not going to think of myself as an artist. I knew better. I knew you have to have diplomas and reviews and sales to be an artist. You can’t just decide you are one.

Then a funny thing happened. I went to that vernissage I was invited to. It was in a gorgeous gallery on the Quai Voltaire, with a stunning view of the Louvre on the other side of the Seine. While I was there, I was introduced to a charismatic older woman, who asked me what I’d been up to in Paris. So I mentioned that I’d taken a class where we did a bit of watercolour painting. She then proceeded to introduce me to everyone there as “Irina, l’aquarelliste.”

I became a little embarrassed at one point, and whispered to her, in whatever French I could muster, that I wasn’t really a watercolour artist, I had just taken my first class two weeks before. “So?” she said, “you’ve done some! And besides, it’s better than saying you’re a professor.”

I laughed, and thought, “Why not?” Then I laughed again at the sheer ridiculousness of me — a woman who as a child failed so spectacularly at an audition for a gifted arts program that she didn’t go near any art classes again for thirty-five years — being introduced to actual real-live artists, people who had decades of good work behind them, as though I did the same thing as they did.

And then, the next morning, I woke up, and my very first thought was, “well, if I’m ‘l’aquarelliste,’ I guess I should paint something.” So I did. It seemed only natural. And that idea — the mere fact that this woman I met once in my life decided to call me an artist — continued to shape what I did. I bought some decent tubes of Sennelier. Once home in Germany I immediately signed up for another watercolour class. I found out where the local art supply stores were. I covered the dining table with paints and pads of paper. I noticed that the street I live on has two artists offering classes — not four minutes from my front door, this time, but about two minutes. I even realised I had an excellent guide to drawing and painting on my own shelf, given to me by one of my closest high school friends for my seventeenth birthday. She was a talented artist who had made it into that gifted arts program, and what she wrote in her playful dedication was, “We are all artistes een r (h)arts.”

In short: I finally accepted it, that idea I could never quite wrap my head around — that you could be an artist just by making art, no matter how well, no matter what amount. I couldn’t be convinced by arguments, but I could be convinced by the playfulness of artists around me. So you could say that it was in Paris that I learned, at last, to be a realist about art.

Irina

Updates

For the New York Review of Books, I reviewed Lea Ypi’s memoir of Albania under Socialism, and in the tumultuous years after the transition to liberalism

In my Times Literary Supplement column, I’ve written about what the Middle English poem Havelok the Dane teaches us about just rulership, St. Leoba’s challenges in guiding a monastery in early medieval Germany, and the short stories of Sholem Aleichem.

And for a forum at Times Higher Education, I contributed a column-length piece of advice for US academics thinking about moving to a European university.

I also recently spoke to the BBC about Mary of Egypt, one of the most compelling and disturbing early medieval saints.

I also chatted to the amazing Anna Gát about the lives of medieval people on her new podcast, The Hope Axis.

Finally, I was delighted to be part of a Medieval Academy of America webinar called, “Writing Against the Clock: Finding Joy in our Writing Practice,” which is now online too.

p.s. I'll be teaching a class on journaling soon and I hope it's o.k. to adapt one of the prompts one of the teachers you had in Paris used--the use of the stencils as a way to generate writing and integrate with drawing...

Wonderful piece! Especially appreciate your final insights: "that you could be an artist just by making art..." I once had a poetry teacher help me overcome my fear of writing poetry by saying: "you write poetry; you're a poet." I do hope you'll get a chance to read and react, in whatever form (perhaps an aquarelle??) to my novel, Cities of Women, about another encounter with art and artists, both medieval and modern. And now, to look for that watercolor class near me...or perhaps pottery??